5 Ways to Improve Aid Transparency

Aid money may never reach people in need. Where is it gone then? From crisis to crisis aid transparency remains an issue with more pitfalls revealed as well as more platforms for tracking funds created. In this article we look at 5 ways to improve transparency in the field.

In the latest report, The First Month: Examining the Humanitarian Relief Response to the 2015 Nepal Earthquakes NGO (DAP), Disaster Accountability Project, examined transparency and effectiveness of aid funding by surveying 100 organizations working in Nepal. They have concluded that it is rather difficult to track where billions of dollars are gone and if donations aimed at Nepal have reached it. Many organizations don’t even conceal the fact that they plan to use money not in Nepal, but somewhere else . Another infamous case is the one of Red Cross Haiti. An investigation revealed that the organization raised nearly half a billion dollars (U.S.) in donations after a destructive earthquake in Haiti, yet built only 6 houses.

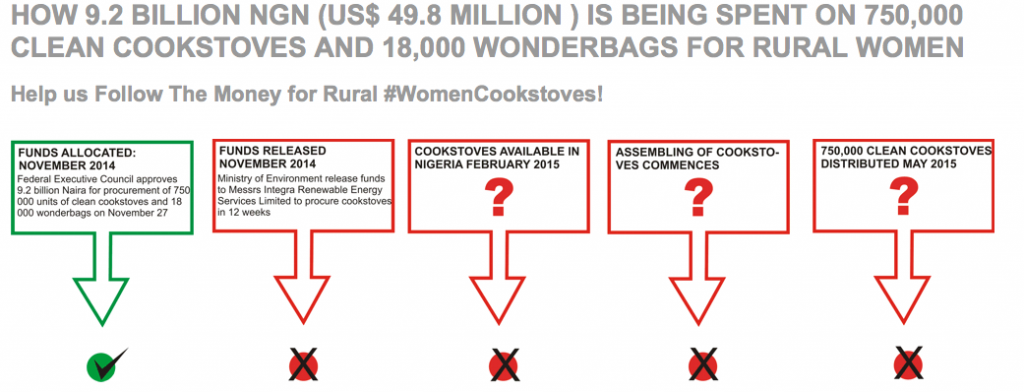

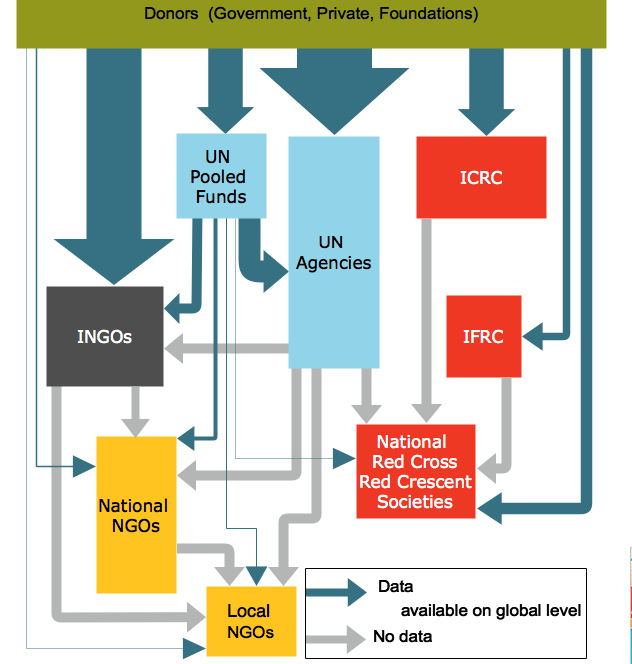

A puzzle of “aid economy” is reflected in graphics created by IRIN that clearly shows – money aimed at locals rarely reach them. Such initiatives as Follow The Money, The Transparency and Accountability Initiative (T/A Initiative) and Aid Transparency Index are amongst efforts to illuminate what is going on in the aid field. Drawing conclusions from a recent discussion on the Guardian global development professionals network, we can see where the weak points in aid transparency are and what should be done.

- Accountability

Demand side is as responsible for transparency and accountability as the supply one. Moreover, “it is the demand side that can stimulate adoption of transparency standards like IATI, ” says Bibhusan Bista, co-founder of YoungInnovations. Bill Anderson, information architect at Development Initiatives, also encourages to distinguish the difference between accountability and operational effectiveness. It also relates to accountability to clients – they should be able to report about quality of aid that they receive. For raising voices and empowering people to take action themselves Accountability Lab initiated Accountability School in Liberia which works particularly with women.

And, finally, donor’s self-reporting and being aware of one’s failures is also pivotal: “Only the successes gets publicized, and the failures get shoved under the carpet (with a degree of generalization),” as development tech entrepreneur Rubayat Khan notes.

- Technological advancement

For increased transparency we need to embrace technology more. Leigh Mitchell, senior development effectiveness adviser at the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development in Myanmar, argues that technologies don’t keep up with the speed of aid field development. “Are donors stuck in the 19th century?” adds Vijaya Ramachandran, senior fellow at Center for Global Development. However, an advanced ICT tool with a fancy look is not really what is needed. The most important is to get data on time and in all details. To reach out and give data “into the hands of “super users’”, namely government and civil society, suggests David Saldivar, Policy & Advocacy Manager at Oxfam America. A good example of a transparent online platform is, for instance, AMP Moldova.

Yet the question with technological advancement is what to do with remote communities that might not have access to ICT. Smartphones have changed situation significantly, but there is still a way to go.

- Timely reporting

Should one report on a daily, weekly or monthly basis? What is important at this very day of crisis won’t make much sense in a few weeks. Thus, daily reporting is essential. We need globally agreed norms on reporting to ensure transparency and efficiency in aid operations, as suggested by Bill Anderson. Dina Abdel-Fattah, associate at Development Gateway, agrees on the point adding that if data was delivered in a consistent and predictable manner it could be “a foundation for decision-making processes”.

- Collaborative approach

“Donors, use your own data – eat your own dogfood,” says Rupert Simons, CEO at Publish What You Fund. He states that this will improve communication flow between countries and decrease possibility for an error in data. Collaboration between donors, government, civil society and aid recipients themselves is the ground for translating data into development. David Saldivar implies that depending on whether the partner countries have accurate data defines to what extent a positive development will take place on the ground.

If there is a lack of collaboration there is also a risk of duplicating aid or missing out on certain zones. “This point could be addressed with geocoding that shows where projects take place and who is involved,” shares experience Dina Abdel-Fattah.

With an upcoming International Conference on Financing for Development that will take place in Ethiopia next week, a collaboration aspect in aid and development will be brought up again.

- Learning

Lack of collaboration and timely reporting can eventually lead to repeating mistakes. Learning from lessons of past disasters as well as engaging recipients would ensure that humanitarian campaigns have expected outcomes. In Nepal alone local organizations have more than 1,560 years of experience working in their own country. Apart from local NGOs, there is also potential in learning from recipients themselves: Leigh Mithchell shows an example of Twitter users in Myanmar inquiring about aid funds on mohinga.info. Meanwhile, they can also be sources of knowledge for international donors on how aid should be operated.

Another case study that should have served for advancing tracking funding is Haiti. A policy paper “Haiti: Where Has All the the Money Gone?” provides some practical solutions for enhancing accountability, which, if taken into account, might help donors to avoid the same mistakes in the future.

Image via Flickr

New PhD opportunities at the University of Leicester

New PhD opportunities at the University of Leicester Call for Abstracts: New Directions in Media, Communication and Sociology (NDiMS) Conference

Call for Abstracts: New Directions in Media, Communication and Sociology (NDiMS) Conference Ørecomm Team to Gather at the University of Coimbra

Ørecomm Team to Gather at the University of Coimbra “Communication and Social Change – A Citizen Perspective” Published

“Communication and Social Change – A Citizen Perspective” Published C4D Network to Sum Up Global Communication for Development Practice

C4D Network to Sum Up Global Communication for Development Practice Entering Media and Communication into Development Conferences?

Entering Media and Communication into Development Conferences? IAMCR Conference 2016: Communication for Development Highlights

IAMCR Conference 2016: Communication for Development Highlights Glocal Classroom Revisited – Storytelling & Social Change Leicester-Malmö

Glocal Classroom Revisited – Storytelling & Social Change Leicester-Malmö I EvalComDev International Conference: Call for Papers

I EvalComDev International Conference: Call for Papers Looking for Media and Communication in Development Conferences: Devres 2016

Looking for Media and Communication in Development Conferences: Devres 2016